- Home

- Portfolios

- Conference

- Research

- IJIKMMENA

- Teaching

- Training

- Consultancy

- Network

- TV

Knowledge Economy

Sustainable Development

SDGs

UN

Agenda 2030

MENA

Algeria

Bahrain

Egypt

Iraq

Jordan

Kuwait

Libya

Morocco

Oman

Qatar

Saudi Arabia

Sudan

Tunisia

UAE

Yemen

Research

Big Interviews

Media

Strategy

Artificial Intelligence

Politics

Government

Business

Training

Investment

Economy

Public Policy

HE

Universities

Startup

Digital Transformation

Technology

KM

Leadership

Learning

Human Capital

Libraries

Gum Arabic

Gamification

GERD

Arab

MENA 2013

Video Ads

LATEST NEWS

- Role of Higher Education in Re-Building the World Economy Post Covid-19

- بحث آفاق التعاون بين اتحاد جامعات العالم الإسلامي والجمعية الدولية للتنمية المستدامة

- Global Business Environments and Entrepreneurship

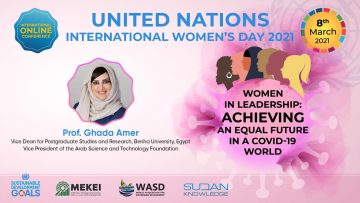

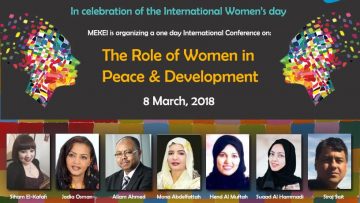

- Role of Women in Peace and Development

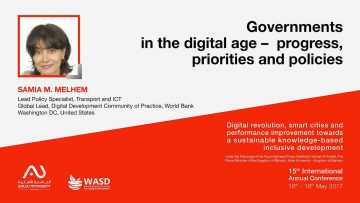

- World Bank Conference on Digital technologies at the service of economic development in the Mediterranean, Marseille, France

- WASD Attends The Kuwaiti Government’s Conference on Knowledge Economy

- Knowledge Management: concepts, process and technology

- OUT NOW: From Oil to Knowledge – Transforming the United Arab Emirates into a Knowledge-Based Economy Towards UAE Vision 2021

-

-

No videos yet!

Click on "Watch later" to put videos here

- View all videos

-

-

-

Experts Network

MEKEI, in conjunction with WASD, has built a strong network of researchers, policy makers, educators, consultants and employers from all parts of the world to exchange knowledge and experience and discuss current developments and challenges. This directory can be used to help find, support and collaborate with experts from the network. Interested in joining the expert directory? Complete the application form. Please check your details in our directory after 48 hrs and if you can not find your name, please contact the directory coordinator at admin@wasd.org.uk. You can also join the expert directories of our sister organisation: World Association for Sustainable Development (WASD) and Sudan Knowledge (SK).

Dr. Anita Häusermann Fábos

Associate Professor Clark UniversityInternational Development, Community, and EnvironmentQualifications:

PhD MA BA

Biography

Anita Fábos is an anthropologist who has conducted research and outreach among refugees and other forced migrants in urban settings in the Middle East, Europe, and the United States. Her scholarship and practice pursues a number of interconnected themes in the area of forced migration and refugee studies: how people make and transform ethnic and racial boundaries and boundary markers, people’s experiences of displacement and challenges to gender norms, historical shifts in citizenship and nationality laws, methods and ethics of research with hidden, vulnerable and mobile populations, transcultural social networks, and refugee narratives and representations. Starting with a lengthy period of action research, NGO activism and outreach in Cairo, Fábos’ research and writing has followed the movements of Muslim Arab Sudanese—her main research participants–from their place of first exile in Egypt, to asylum in Europe and North America, and towards the formation of a diaspora straddling Islamic ‘space’ (countries in which Islam is the religion of the state) and the ‘asylum space’ of countries of resettlement in Europe and North America. As the Director of the Forced Migration and Refugee Studies program at the American University in Cairo, and later Programme Coordinator for the graduate program in Refugee Studies at the University of East London, Fábos has been involved in developing integrated teaching, research, and outreach programs that have incorporated refugee and forced migrant perspectives into collaborative work with scholars, practitioners, refugee organizations, policy makers, and international organizations. At Clark University, students in her classes have carried out community-based projects that have investigated refugee participation in community development initiatives, refugee access to higher education, and refugee livelihoods in Worcester. Fábos is currently conducting ethnographic research on the transnational strategies of women and men in the Muslim Arab Sudanese diaspora to promote ‘family values’ and negotiate a Sudanese diasporic identity, particularly in the context of global Islam. Other projects include an edited collection on the relevance of a ‘spiritual geography’ of Islam on forced migration within the Muslim world in a time of intensifying discourse of ‘security’; a special issue of Home Cultures that interrogates ‘home-making’ in protracted refugee situations; and an exploration of wedding singers and the performance of Sudanese music in the Muslim Arab Sudanese diaspora.

Worcester USA